- Long COVID is horrible, ruins lives, and there is no cure for it yet.

- Yes, current evidence indicates that covid-19 vaccines can reduce risk for long-COVID and do not exacerbate existing long COVID.

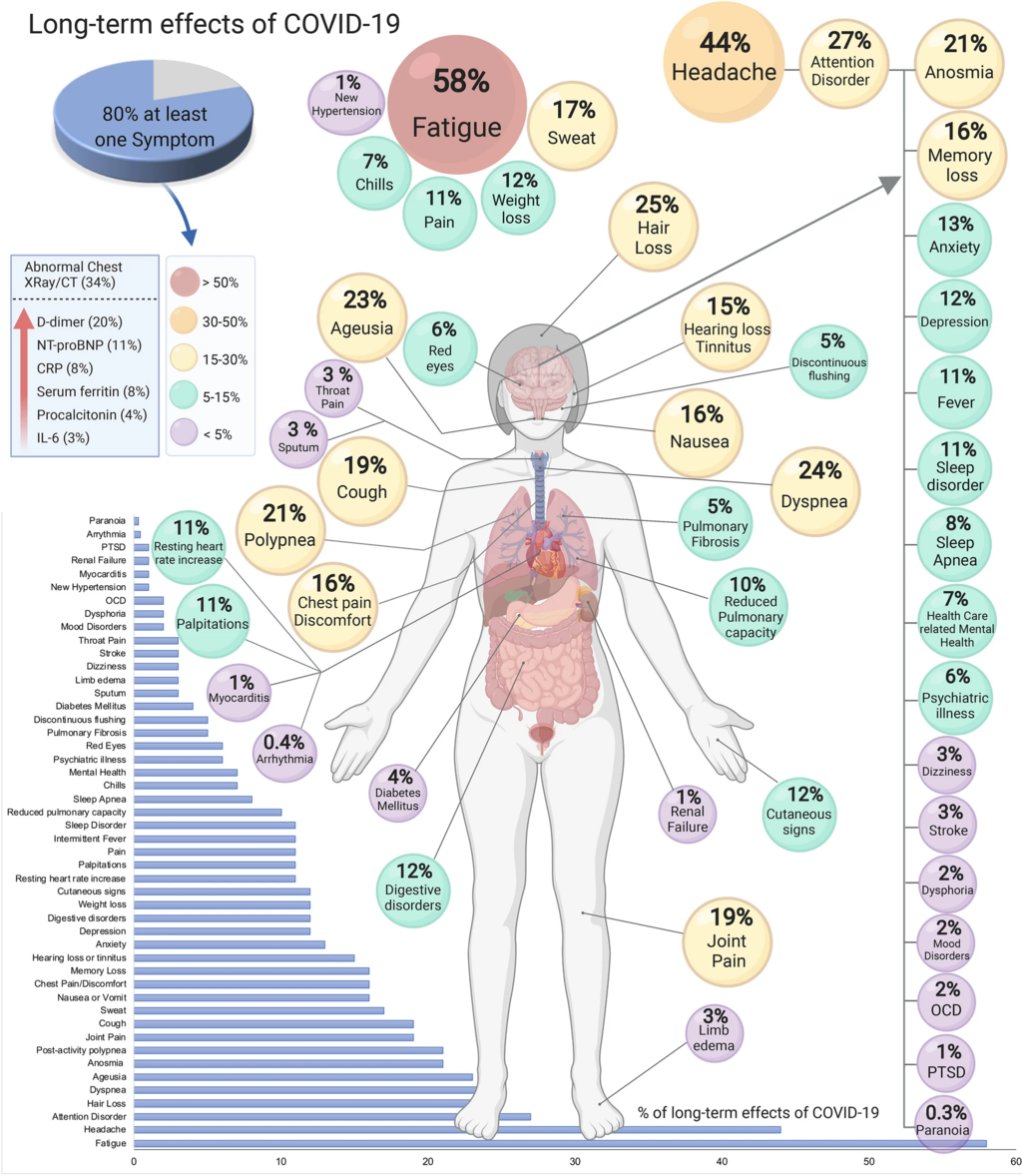

One of the most perplexing health challenges associated with the COVID-19 pandemic is the enigmatic condition known as long COVID. As the name suggests, it refers to a multitude of symptoms and conditions that persist beyond three-months after someone has been infected with the virus. These symptoms cannot be explained by other diagnoses, making it a puzzle that continues to baffle researchers and healthcare professionals alike.

Early in the pandemic was the observation on long COVID was its association with the severity of the initial COVID-19 infection. Those who endured severe COVID-19 infections seemed to be at a higher risk of experiencing the lingering effects of long COVID. It is as if the virus leaves a deeper impact on those who faced a more formidable battle with it. But severe disease is but one risk factor. Anyone who gets infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus can develop long COVID no matter how young, fit, and health they are.

Here are the predictors of getting long COVID:

- Female sex

- Older age

- Smoker

- Pre-existing medication condition(s)

- No COVID-19 vaccination

- Infection with pre-Omicron variant

- Number of symptoms while ill

- Viral load

- Severe/critical COVID-19 (hospitalised)

- Needing invasive mechanical ventilation

What are the symptoms?

The main symptoms are listed below and develop from three months after acute COVID-19 disease and last for at least two months afterwards. These symptoms cannot be explained by anything else. (From the WHO clinical case definition)

These develop after initial recovery from acute SARS CoV 2 infection or persist from the original illness. They may fluctuate or even relapse over time, they impact everyday functioning, and they encompass (in descending order of ≥50% agreement):

- Fatigue (78%)

- Dyspnea (78%) – this is difficulty breathing

- Cognitive impairment/brain fog (74%) – essentially, this is brain damage

- Post-exertional malaise (67%) – small effort leaves you exhausted

- Memory issues (65%) – hello dementia

- Muscle pain/spasms (64%)

- Cough (63%)

- Sleep disorders (62%)

- Tachycardia/palpitations (60%) – heart doing weird speedy things

- Altered smell/taste (57%)

- Headache (56%)

- Chest pain (55%)

- Joint pain (52%)

- Depression (50%)

This all sucks and it ruins lives. Can we prevent it?

Image credit: Authors of the study: Sandra Lopez-Leon, Talia Wegman-Ostrosky,

Carol Perelman, Rosalinda Sepulveda, Paulina A. Rebolledo, Angelica Cuapio &

Sonia Villapol, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Vaccines can make a positive difference

Let’s consider where we are now in the pandemic. The ancestral variant, Alpha, and Delta are all relegated to obsolescence. Today is the reign of Omicron and decedents with less memorable names such as XBB and B4-5. The good news is that Omicron has been associated with a lower risk for developing long COVID.

Vaccines have shown promise in reducing the occurrence of long COVID. Studies have indicated that individuals who have been vaccinated are less likely to experience long COVID after a breakthrough infection compared to those who remain unvaccinated.

Yet, as we delve further into the realm of long COVID and vaccines, we encounter challenges in measuring it. Studies investigating the effectiveness of vaccines against long COVID vary widely in their methodologies, the types of vaccines considered, and the populations they focus on. This diversity makes it difficult to draw sweeping generalisations about the relationship between vaccines and long COVID.

- What variant was circulating at the time of the study?

- Did the people in the study have vaccine immunity, hybrid immunity, no prior immunity?

- Were the people in the study healthy and young? Were they elderly? Were they hospitalised?

Different studies utilise different methods, such as observational studies, clinical trials, or surveys, and can measure different outcomes. Moreover, vaccines themselves come in different forms, such as mRNA, viral vector, or protein based. The efficacy of each vaccine against long COVID may differ, and this complexity adds to the challenge of arriving at a clear-cut conclusion. It is a hard disease to define, and it is hard to study in a rapidly changing landscape of new variants and changing immunity.

A recent (Feb 2023) systematic review and meta-analysis of the relationship between any type of COVID-19 vaccination and long COVID provides a good summary. Here are the main findings:

- A total of 629,093 patients were studied.

- Two doses vs. no dose prior to infection ~36% less likely.

- Two doses vs. one dose prior to infection ~40% less likely.

- One dose vs. no dose prior to infection ~10% less likely.

- No evidence that vaccination given to long COVID patients resulted in deterioration of symptoms and there was limited evidence that it may result in an improvement.

A more recently published (July 2023) systematic review and meta-analysis concurred with these results.

Outstanding questions

There is limited evidence on the role of booster doses, vaccine formulations, and effect against long COVID caused by the new variants. There is also limited evidence on the risk for people who have a greater variety of immune status, such as hybrid immunity and booster status. Only time will tell.

Resources and further links

Are you in NZ? Do you have long COVID?

Here is a NZ registry, please join and be counted.