Today’s episode: The one about the strokes after COVID-19 vaccine

- Déjà Vu, anyone? – Once again, we have a “study” rising from the crypt. This is the misuse of VAERS data like a broken record. This time the claim is that COVID-19 vaccines are out to get us by causing strokes.

- Shocking stats… That do not mean much – Claims like "112,000% increase in brain clots!" are terrifying, sure. But without proper context, they’re like saying “shark sightings are up 10,000%” after one trip to the beach cos you saw a shark. Scary on paper, useless in reality.

- Zombie myth #101: Ignoring the fine print – VAERS warns you right upfront: it’s a tool for spotting signals, not proving cause and effect.

- What real scientists would do – They would start with a clear hypothesis; use verified data and rely on rigorous analysis. They would avoid turning a suggestion box into a megaphone for vaccine myths.

- Misinformation gone viral – Sadly, this recycled scare tactic has found new life on social media, where cherry-picking data is an art form, and context is the ultimate casualty.

An unscientific study misuses Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) data—a self-reported system meant for early signal detection, not proof of causation—to claim that COVID-19 vaccines carry a dramatically higher risk of brain clots. Despite VAERS’s well-known limitations, the study jumps to alarming conclusions, and even calls for a global halt on COVID-19 vaccines. Conspiracy theorists on social media snapped up the dramatic claims and exaggerated risk with sensational figures (e.g., "112,000% increase in brain clots!"). As in so many cases of deliberate generation of disinformation, this baloney has gone viral. The misuse and abuse of data have become more fuel for anti-vaccine narratives, that spread fear and distrust based on unverified, fallacious interpretations.

Check the facts

Myth: A peer-reviewed study demands an immediate global suspension of COVID-19 vaccines.

![]() Fact-check: Nice try, but no. This study relies on VAERS data, which is a self-reported system that explicitly warns it shouldn’t be used to prove cause and effect. VAERS is for picking up weak signals, not screaming fire. Calling for a global halt to vaccination based on this unverified, anecdotal data is reckless fearmongering, not science.

Fact-check: Nice try, but no. This study relies on VAERS data, which is a self-reported system that explicitly warns it shouldn’t be used to prove cause and effect. VAERS is for picking up weak signals, not screaming fire. Calling for a global halt to vaccination based on this unverified, anecdotal data is reckless fearmongering, not science.

Myth: The study found a “horrifying” increased risk of brain clots after COVID-19 vaccination.

![]() Fact-check: “Horrifying”? Social media does the dramatics here. The study used VAERS reports—a dump of unconfirmed, self-reported claims that anyone can submit. Using VAERS to draw firm conclusions is like diagnosing cancer based on WebMD symptoms—it’s wildly irresponsible. Scientists use VAERS as a starting point, not a final answer, and no one with real expertise would scream “horror” over this data alone.

Fact-check: “Horrifying”? Social media does the dramatics here. The study used VAERS reports—a dump of unconfirmed, self-reported claims that anyone can submit. Using VAERS to draw firm conclusions is like diagnosing cancer based on WebMD symptoms—it’s wildly irresponsible. Scientists use VAERS as a starting point, not a final answer, and no one with real expertise would scream “horror” over this data alone.

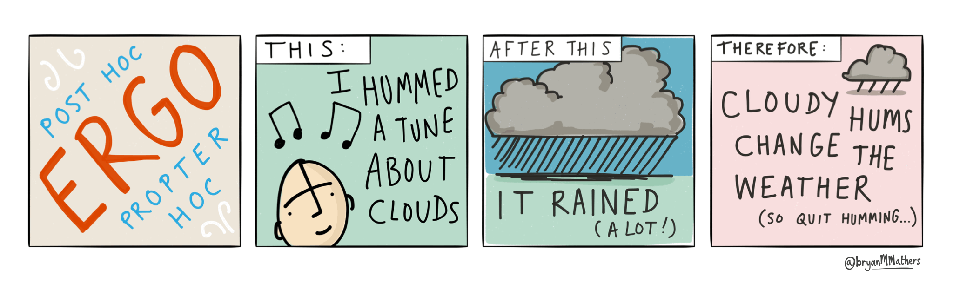

This is a fallacy of the Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc (False Causation): This fallacy occurs when it is assumed that because one event followed another, the first event must have caused the second. In this case, people often misuse VAERS data by suggesting that just because a health event (like a symptom or condition) was reported after vaccination.

Post hoc ergo propter hoc by @bryanMMathers is licensed under CC-BY-ND.

Myth: COVID-19 vaccines are 112,000% more likely to cause brain clots than flu shots!

![]() Fact-check: Scary numbers, right? And also meaningless without context. VAERS data does not confirm causation, does not account for how many people got each vaccine, and does not account for reporting biases. These claims about "percentages" are like saying “rainfall is up 1,000%” after a light drizzle during a drought—technically true, but completely misleading.

Fact-check: Scary numbers, right? And also meaningless without context. VAERS data does not confirm causation, does not account for how many people got each vaccine, and does not account for reporting biases. These claims about "percentages" are like saying “rainfall is up 1,000%” after a light drizzle during a drought—technically true, but completely misleading.

Myth: COVID-19 vaccines are 20,700% more likely to cause brain clots than all other vaccines combined.

![]() Fact-check: Seriously? These figures are built on a wobbly house of cards. VAERS data has no denominator, no way to calculate real risk, and no controls for different populations. Comparing COVID-19 vaccine reports to decades of other vaccine data without context is the epidemiological equivalent of saying “cars today are 10,000% more dangerous than horse-drawn carriages”—it’s nonsense and misleads people about the actual science.

Fact-check: Seriously? These figures are built on a wobbly house of cards. VAERS data has no denominator, no way to calculate real risk, and no controls for different populations. Comparing COVID-19 vaccine reports to decades of other vaccine data without context is the epidemiological equivalent of saying “cars today are 10,000% more dangerous than horse-drawn carriages”—it’s nonsense and misleads people about the actual science.

Myth: The study calls for a total COVID-19 vaccine moratorium and an “absolute contraindication” for women of reproductive age.

![]() Fact-check: This is pure alarmism dressed up as research. The authors used data from VAERS—again, an unverified, self-reported system that explicitly warns against drawing these kinds of conclusions. Public health decisions require evidence from controlled studies, not cherry-picked data from a suggestion box published by people with no relevant expertise in vaccine safety science. Demanding a moratorium based on this is irresponsible and completely out of line with scientific standards.

Fact-check: This is pure alarmism dressed up as research. The authors used data from VAERS—again, an unverified, self-reported system that explicitly warns against drawing these kinds of conclusions. Public health decisions require evidence from controlled studies, not cherry-picked data from a suggestion box published by people with no relevant expertise in vaccine safety science. Demanding a moratorium based on this is irresponsible and completely out of line with scientific standards.

Myth: A full investigation is needed because safety thresholds have been breached, and regulators have ignored these risks.

![]() Fact-check: Regulators have not “ignored” anything. COVID-19 vaccines are under constant, intense safety monitoring worldwide using real data and verified reporting systems. VAERS is just one piece of the puzzle, not the whole picture. Claiming an “alarming breach” based on this flimsy data is like calling the fire department every time you burn toast—it’s irresponsible and distracts from real issues.

Fact-check: Regulators have not “ignored” anything. COVID-19 vaccines are under constant, intense safety monitoring worldwide using real data and verified reporting systems. VAERS is just one piece of the puzzle, not the whole picture. Claiming an “alarming breach” based on this flimsy data is like calling the fire department every time you burn toast—it’s irresponsible and distracts from real issues.

Myth: Regulators and manufacturers must be held accountable for ignoring these risks.

![]() Fact-check: This is flat-out misleading and uses the Appeal to Ignorance logical fallacy. This fallacy implies that because certain risks are perceived to be ignored, they must not be addressed, disregarding evidence that regulators are actively monitoring vaccine safety. Regulators are actively monitoring vaccine safety using multiple, sophisticated systems—not just VAERS. VAERS is an early warning system, not a definitive source. Suggesting a conspiracy because regulators don’t act on every VAERS report is like blaming a weather forecaster for not evacuating a city over a cloudy day. It’s scientifically illiterate and spreads unnecessary fear.

Fact-check: This is flat-out misleading and uses the Appeal to Ignorance logical fallacy. This fallacy implies that because certain risks are perceived to be ignored, they must not be addressed, disregarding evidence that regulators are actively monitoring vaccine safety. Regulators are actively monitoring vaccine safety using multiple, sophisticated systems—not just VAERS. VAERS is an early warning system, not a definitive source. Suggesting a conspiracy because regulators don’t act on every VAERS report is like blaming a weather forecaster for not evacuating a city over a cloudy day. It’s scientifically illiterate and spreads unnecessary fear.

What real scientists would do

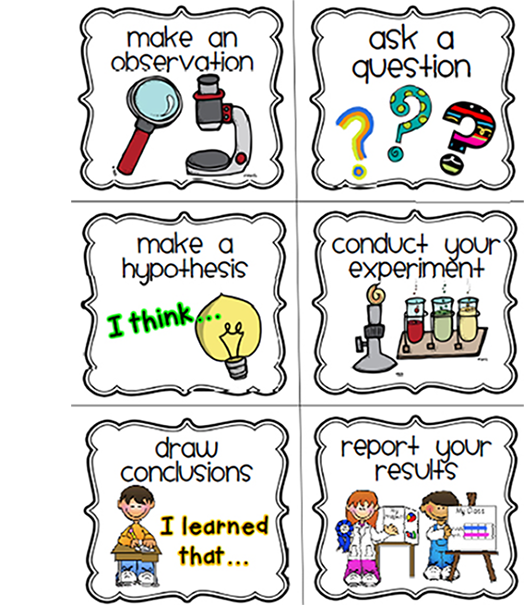

Here’s a brief list of steps that real scientists would follow to investigate potential vaccine side effects properly, starting with the basics of the research question and hypothesis:

1. Define a clear research question

Example: "Does the COVID-19 vaccine increase the risk of cerebral thromboembolism compared to other vaccines?"

2. Develop a testable hypothesis

Example: "Individuals receiving the COVID-19 vaccine have a higher incidence of cerebral thromboembolism than those receiving other vaccines."

3. Select an appropriate study design

Use a design that minimises bias and allows for causal inference. A self-controlled case series (SCCS) method, for example, is particularly effective for vaccine safety studies. It compares individuals’ health outcomes during “risk” periods after vaccination to other “control” periods within the same individuals, reducing confounding variables.

4. Establish a verified data source

Use active surveillance databases that provide a true denominator and verified reports, like the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) or the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) if you are in the U.S. This ensures accurate incidence rates.

5. Conduct data analysis with proper controls

For SCCS, carefully define the “risk period” following vaccination and compare this to pre- or post-risk periods within the same individual, accounting for individual variability and eliminating time-invariant confounders.

Image source: Promega Connections

6. Interpret results in context

Use statistical tests to evaluate whether any observed increase in adverse events is statistically significant and medically relevant. Ensure transparency about any limitations or potential biases in the study.

7. Seek peer review and replication

Submit findings to a journal where peer-reviewers are experts in the field of vaccine safety surveillance study methodologies and encourage replication by independent researchers, as confirmation across studies is essential for scientific validity.

RINSE AND REPEAT ELSWHERE BY OTHERS

By following these steps, scientists ensure that their conclusions are based on reliable data, robust methods, and rigorous analysis, leading to findings that can genuinely inform public health decisions.

Interested in more detail? Keep reading ...

The research question

Scientific research always has a clearly defined question. The research question here is vague to non-existent. The article describes:

“The purpose of this report is to query the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) for the safety signals of venous/arterial thromboembolism after vaccination.”

However, the article did not clearly state a formal hypothesis, which is typically expected in scientific research. A well-defined hypothesis would look something like:

“COVID-19 vaccines increase the risk of cerebral thromboembolic events compared to other vaccines.”

Instead, the article jumps directly into analysing VAERS data without setting up a testable hypothesis.

What the researchers did

The researchers' decision to use VAERS data to draw definitive conclusions about the risks associated with COVID-19 vaccination, especially given VAERS’s well-documented limitations, raises serious concerns about the appropriateness and scientific rigor of their study. VAERS itself explicitly warns against using its data to assess causation or calculate actual incidence rates due to the lack of a true denominator, underreporting, reporting biases, and the unverified nature of the reports. Instead, VAERS is intended as an early-warning system to detect potential safety signals that require further investigation through more robust, controlled studies such as this one from Lu et al.

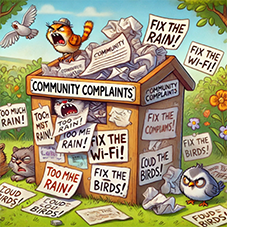

VAERS is like a community suggestion box at a busy store, anyone can drop a note in but you also need to know how many people shopped there to make any meaning of it.

VAERS is like a community suggestion box at a busy store, anyone can drop a note in but you also need to know how many people shopped there to make any meaning of it.

Using VAERS for purposes it explicitly cautions against—such as determining causation or recommending a “global moratorium” on COVID-19 vaccines—is a significant misuse of the data. This approach disregards the inherent biases in VAERS data, such as heightened reporting for COVID-19 vaccines due to intense public attention and concerns, which can skew results. By ignoring these caveats, the researchers risk inflating the perceived risk associated with COVID-19 vaccines and drawing unwarranted conclusions. In other words, when using raw, unverified data, the conclusions are only as reliable as the data itself. Read more about What VAERS is (and isn't).

In scientific research, it's critical to select data sources appropriate for the research question and the level of evidence required to support claims. VAERS data, by design, are not sufficient to establish causality or quantify risk reliably. Using it to support sweeping public health recommendations undermines the credibility of the research contributes misinformation. For a study on vaccine safety to be robust and valid, it should rely on data sources that allow for controlled comparisons and have verified adverse event reports, such as active surveillance systems (e.g., the Vaccine Safety Datalink at the Center for Disease Control and Prevention) or well-designed cohort studies.

by design, are not sufficient to establish causality or quantify risk reliably. Using it to support sweeping public health recommendations undermines the credibility of the research contributes misinformation. For a study on vaccine safety to be robust and valid, it should rely on data sources that allow for controlled comparisons and have verified adverse event reports, such as active surveillance systems (e.g., the Vaccine Safety Datalink at the Center for Disease Control and Prevention) or well-designed cohort studies.

Relying on VAERS for purposes it was not intended for not only misrepresents the data but also ignores established scientific standards. Researchers have an ethical and professional responsibility to use data appropriately, especially in areas as impactful as vaccine safety. Ignoring these limitations in favour of sensational conclusions does a disservice to both science and public health.

VAERS has even received a report from an individual claiming a vaccine had turned him into the Incredible Hulk. Of course, this report was not a legitimate account of a vaccine side effect rather to prove a point that anything can be reported to VAERS. It serves as a reminder of the importance of critical analysis when interpreting data from open self-reporting systems.

Other considerations

Source

The Journal is low impact and does not specialise in pharmacoepidemiology or vaccines therefore may not have a suitable network of qualified peer reviewers in this discipline.

Author qualifications related to vaccine safety science

The authors include Claire Rogers, James Thorp, Kirstin Cosgrove, and Peter McCullough. Rogers and Cosgrove are noted as independent researchers, and Thorp and McCullough have affiliations with The Wellness Company and the McCullough Foundation, respectively. The credentials listed for these authors do not indicate specific expertise in epidemiology, pharmacovigilance, or data science related to vaccine safety. This raises flags as to the rigor and neutrality of the analysis. Notably, Peter McCullough is a public figure well known for his scepticism and misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines, which may suggest a potential bias. There are also some citations in the article from dubious or controversial sources, including blogs and preprint studies, which also reduces the overall credibility of the research.

Appropriateness of the methods to assess possible causal associated between COVID-19 vaccines and stroke

The study employs a retrospective cohort analysis using data from VAERS. While the VAERS system is a valuable tool for identifying potential safety signals, it has significant limitations. VAERS is a passive reporting system, meaning it is subject to underreporting and lacks the capacity to confirm causation. Use of proportional reporting ratio (PRR) analyses to compare VAERS reports for different vaccines raises methodological concerns due to potential reporting biases, especially given heightened attention to COVID-19 vaccines, lack of denominator, and not accounting for differences in vaccine administration rates, populations, or time periods.

“…disproportionality cannot be used for comparative drug safety analysis beyond basic hypothesis generation because measures of disproportionality are: (1) missing the incidence denominators, (2) subject to severe reporting bias, and (3) not adjusted for confounding. Hypotheses generated by disproportionality analyses must be investigated by more robust methods before they can be allowed to influence clinical decisions.”

The lack of a true denominator in the VAERS dataset is a critical limitation that significantly impacts the reliability of this study’s conclusions. VAERS, being a passive reporting system, collects reports of adverse events (AEs) without tracking the total number of individuals vaccinated. This lack of a denominator means it is not possible to calculate the actual incidence rate of adverse events per vaccinated person, which is essential for making meaningful comparisons.